Halfway

to the Slovak State

Munich Agreement

29. 9. 1938

The First World War changed the landscape of Europe. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the First Czechoslovak Republic was established. Slovakia, as a part of the republic, first faced the aftermath of the war and later the Great Depression caused by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which exacerbated the internal political conflicts on our continent. In 1933, Adolf Hitler won the German general elections and became the new Reich Chancellor, an event that would determine the course of European history for the next decade..

The year is 1938 and Nazi Germany in the so-called Anschluss annexes Austria. Hitler doesn't hide his intentions to seize the neighbouring Czechoslovakia.

Hitler is trying to break up Czechoslovakia, which as a democratic country offered a refuge to the opponents of Nazism. Hitler was raising territory claims, willing to proceed through international political agitation or resort to military action. He was definitely playing the German population card - Germans living and allegedly suffering from discrimination beyond the German borders - a similar excuse as he used when he annexed Austria. It suited him that the territory of Slovakia (a relatively uninteresting country for Hitler at the time) was eyed by both Poland and Hungary. The Sudetenland and the border areas of Czechoslovakia, inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, are at stake now.

Germany, Italy, Great Britain and France convened in Munich on 29 September 1938, where they decided on the fate of Czechoslovakia without its presence at the table. The Republic must cede Sudeten territory to Germany. The Czechoslovak government was particularly surprised by the attitude of their allies, France and Great Britain, but did not have any other options. A day later, on 30 September 1938, they accepted the decision, which went down in history as the Munich Agreement, sometimes called the Munich Dictate. It was one of the heralds of the coming war, before which, however, Slovakia went through several drastic political changes.

Hlinka's Slovak People's Party

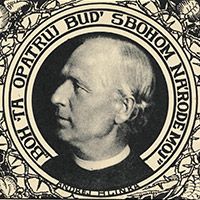

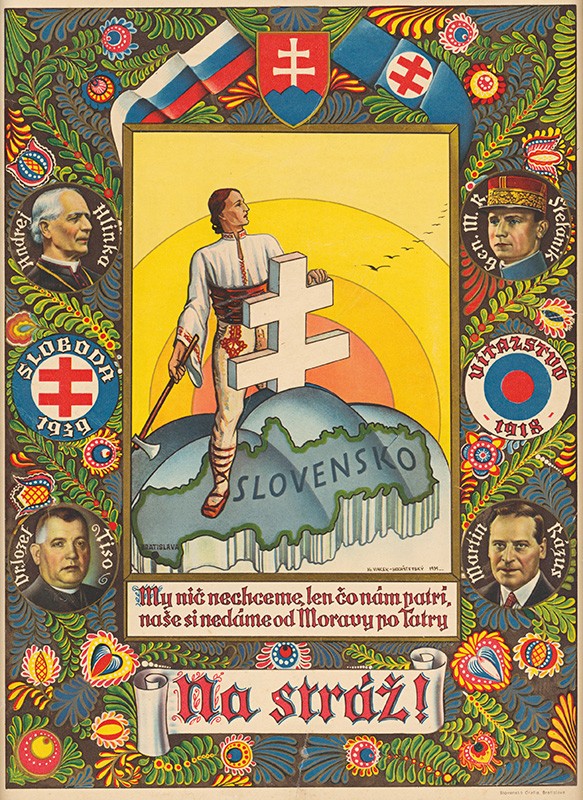

At the time of the Munich Agreement, the most influential political party in Slovakia was Hlinka's Slovak People's Party (HSPP), which in 1935 in coalition with the Slovak National Party won 30% of the votes in the elections. It was founded as Slovak People's Party in 1905, then restored by a Catholic priest and a nationalist, Andrej Hlinka. It was founded on conservative Christian values and slowly but surely became obsessed with the idea of autonomy - an independent Slovakia within the Czechoslovak Republic.

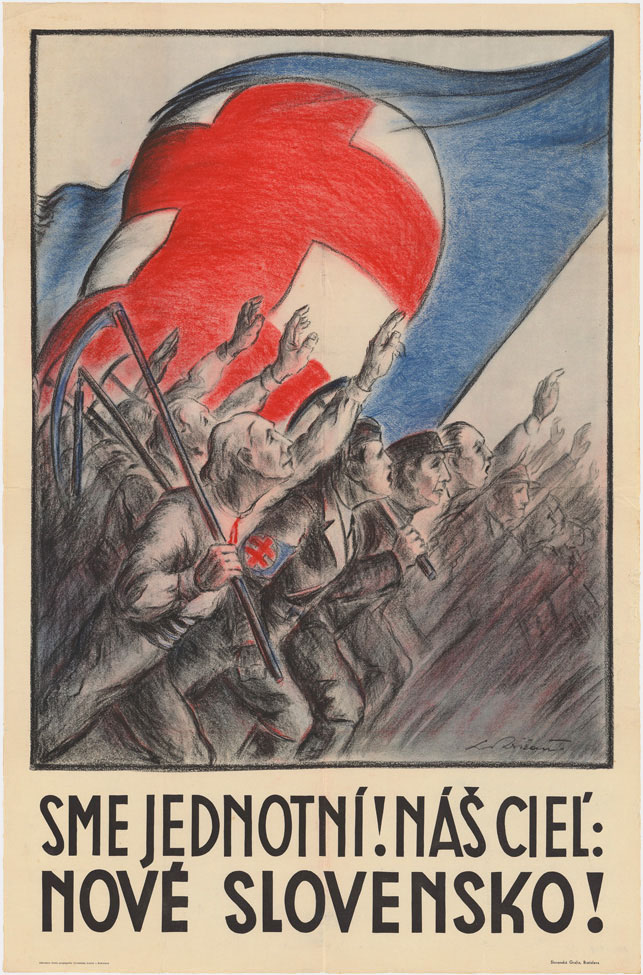

The HSPP's gradual radicalisation was epitomised by their totalitarian motto: "One Nation, One Party, One Leader."

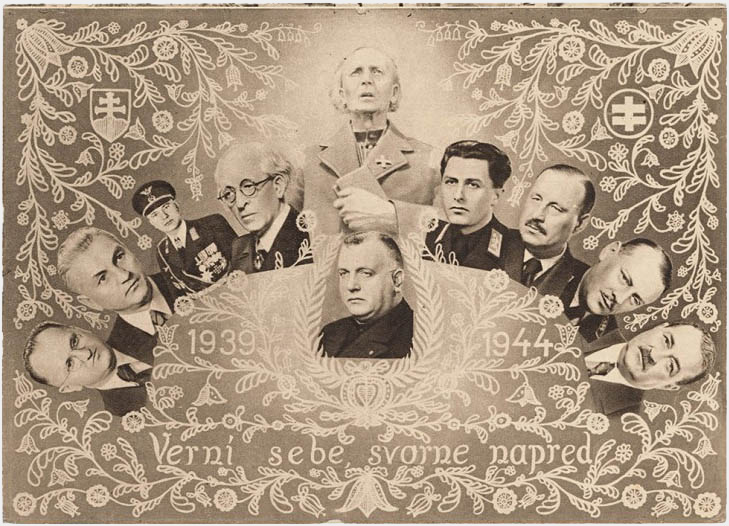

During October 1938, the HSPP strived to solve the issue of Slovakia within the Republic and pushed for autonomy. Within the party, there were two conflicting approaches, the so-called moderate wing (represented mainly by Jozef Tiso, Jozef Sivák and Martin Sokol) and the radical wing (led by Vojtech Tuka, Ferdinand Ďurčanský and Alexander Mach). They differed in their views on autonomy and disagreed on antisemitic legislation. What was the answer of "one nation, one party and one leader" - soon to be Jozef Tiso - to these burning questions?

Find out more about the figures of the HSPP

Declaration of Slovakia’s Autonomy

6. 10. 1938

The Munich Agreement had immediate social and political consequences for Central and Eastern Europe. According to German analysis, requested by Adolf Hitler in October, Slovak people had four options:

- declaring independence and founding their own state,

- declaring autonomy within the Czechoslovak Republic,

- declaring autonomy with a focus on Hungary and a possible merger with their southern neighbour,

- declaring autonomy with a focus on their northern neighbour, Poland.

On 6 October 1938, HSPP officials met in Žilina with representatives of smaller political parties to introduce their proposal for Slovak autonomy within the Czechoslovak Republic. In the documents presented at the Žilina Conference, the HSPP claimed that Slovakia welcomes a "peaceful solution to the problem in the spirit of the Munich Agreement." In their manifesto, the party welcomed the Munich Agreement and emphasised their commitment to "stand by the side of nations fighting against the Marxist-Jewish ideology of disruption and violence." They also insisted on "immediate transfer of executive and governmental control to the Slovak people." It soon became clear that according to the HSPP politicians, they were the only legitimate representatives of the Slovak people.

On 7 October 1938, the Czechoslovak government accepted the proposal by the HSPP. Jozef Tiso was declared the Prime Minister of the Autonomous Slovak Region.

The National Assembly met on 19 November 1938 and affirmed Slovak autonomy through a new constitutional law. Czechoslovakia gained a hyphen in its name and thus became the Czecho-Slovak Republic. From this moment, Slovakia is facing another challenge - rising demands from Hungary and Poland. At a meeting in Komárno, the Czecho-Slovak side, led by Tiso and without a clear strategy, started negotiations with Hungary. These negotiations lasted until November 1938 and resulted in the First Vienna Arbitration, in which Slovakia lost parts of its territory.

First Vienna Award

2. 11. 1938

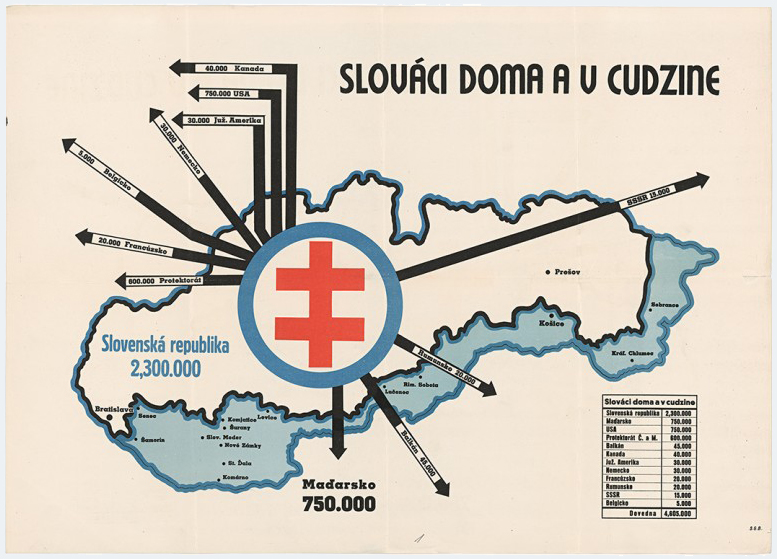

The Munich Dictate cost the Czechoslovak Republic the territories occupied by the Germans. Because an appendix to the Munich Agreement spoke about solving the problem of Hungarian and Polish minorities within three months of signing, it became clear that Slovakia would have to address the Hungarian territorial claims very soon. On the table was a fifth of the territory of Slovakia, including Carpathian Ruthenia and 854,218 inhabitants of this region, including 272,145 Slovak and Czech nationals.

The official negotiations between the Czecho-Slovak and Hungarian sides did not lead to a clear decision. Both countries turned to the signatories of the Munich Agreement and the large areas of Slovakia were annexed by Hungary in the First Vienna Award.

Based on the Munich precedent, Poland also claimed their piece of land, which included several villages of Orava, Kysuce and Spiš. The Slovak population that remained in their homes in the newly acquired parts of Hungary immediately became a target of oppression, humiliation, violence and even open persecution. The state was able to evacuate and shelter 50,000 Slovaks. Other people fleeing to Slovakia due to the bad conditions became refugees. According to some estimates, up to 100,000 people took refuge in Slovakia during 1938 and 1943 and became dependent on charity and state benefits after fleeing from Hungary. The number of emigrants from Slovakia to Hungary was significantly lower, since there were very few Hungarian nationals living outside the contested territories. On the initiative of the HPSS, after the declaration of autonomy a further 9,000 Czech state employees and teachers were deported, including those who voluntarily came to help out a country which did not have sufficient resources by itself.

Shortly after the declaration of autonomy, verbal attacks on Jewish minorities escalated and from 4 November, the populist regime organised the deportation of more than 7,500 people from Slovakia to the annexed territories. The government also started preparing of the anti-Semitic legislation, under the leadership of Karol Sidor.

Autonomous Slovak Diet Elections

18. 12. 1938

The autonomous government called for elections to the Diet of the newly created Slovak Region on Saturday, 26 November 1938, with the date of the election on 18 December 1938. Since the lists of candidates were required to be submitted three weeks before the election, the last day of submission was Sunday, 27 November 1938. This way, the HSPP ensured that the list of candidates of the Hlinka Slovak People’s Party - Party of Slovak National Unity would be the only one accepted. Their list of candidates included the representatives of affiliated parties and minorities, but excluded the unwanted Czech and Jewish minorities. Under the pretence of "national unity", they started suppressing the freedom of the press and the freedom of assembly.

Shortly before the elections, the Ministry of Interior issued secret instructions, according to which regions with ethnically mixed population should create special polling stations for the various nationalities to more easily determine how each of them voted.

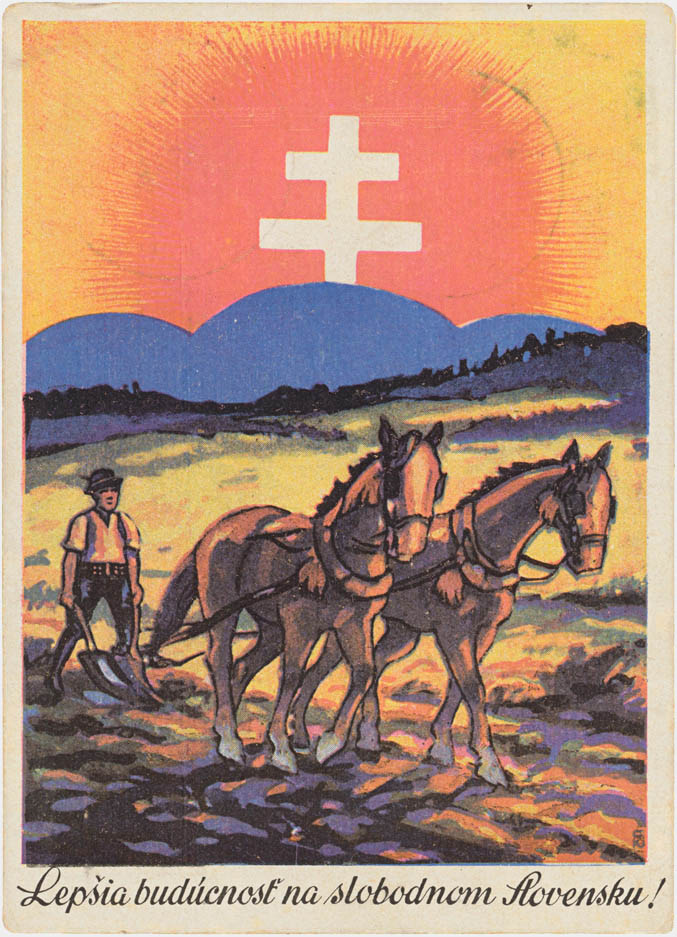

In elections, where one cannot choose a political party, but merely accept or reject the suggested list of candidates, 97,3% of voters replied positively to the suggestive question: "Do you want a new and happy Slovakia?"

Creation of the Slovak State

14. 3. 1939

Although Adolf Hitler had a hand in the events that took place in the Slovak territory in 1938, his final goal wasn't annexation of Czech borderlands or Slovak autonomy. His next step was the division of Czecho-Slovakia and the annexation of Bohemia and Moravia to the German Reich. It could not happen through military occupation, since Germany promised to guarantee security and integrity of the shrunken Czechoslovakia in the Munich Agreement. If, however, Slovakia declared independence and Czecho-Slovakia ceased to exist, the former terms of agreement would no longer apply and Germany could occupy the desired territories without risking conflict with the other powers. The HSPP was going to help Hitler execute his plan...

The radical wing of the HSPP, represented by Vojtech Tuka, Alexander Mach and Ferdinand Ďurčanský, met with the German diplomats several times at the turn of 1938 and 1939 without the knowledge of the Slovak government. They presented the idea of declaring independence as unproblematic.

Tuka declared during a visit with Hitler: "My leader, I put the fate of my nation into your hands. My nation wants you to liberate them."

At home, the government, the Diet and the leadership of the HSPP rejected the proposition of the radicals since they envisioned the graduation to an independent state in the distant future through a natural revolution rather than Tuka’s revolution. In line with Hitler's interest, the Czecho-Slovak government in Prague found out about the Slovak desire for independence and responded by military action on 9 March 1939. They declared military dictatorship in Slovak, Jozef Tiso is dismissed from his post as the Prime Minister and Karol Sidor, Tiso's HSPP colleague, was named as his successor.

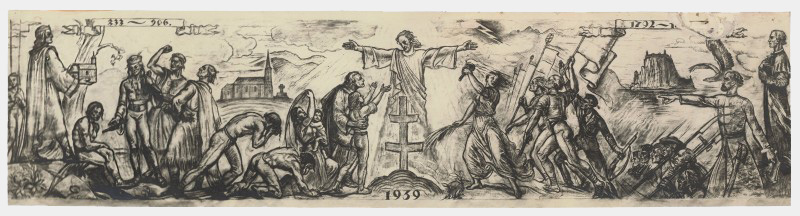

After Sidor rejected the pressure from the Nazis to declare independence, Hitler invited Jozef Tiso to Berlin, where he threatened him that if Slovakia did not declare independence (in the next few hours), he would "abandon Slovakia to its fate". This fate might have been a division of the territory between its three neighbours - Germany, Poland and Hungary, whose troops were allegedly already moving to the borders. Despite the fact that Jozef Tiso was not an official representative of Slovakia at the moment, with Hitler's support he able to ask the president Emil Hácha to call the Diet on 14 March 1939. At the meeting, the Slovak Diet declared the creation of the Slovak State and Hitler's troops entered the Czech territories the next day, declaring the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, within the German Reich. The newly created Slovak State was facing the five years of its existence, marked by the Second World War.

Learn more about the anthem

All artworks in this chapter can also be found in the collection at the Web of Art: Halfway to the Slovak State.